When discussing climate action in India today, from solar transitions to forest conservation and net-zero goals, we often overlook that the country’s first line of defence was never a policy, budget, or summit.

It was the people.

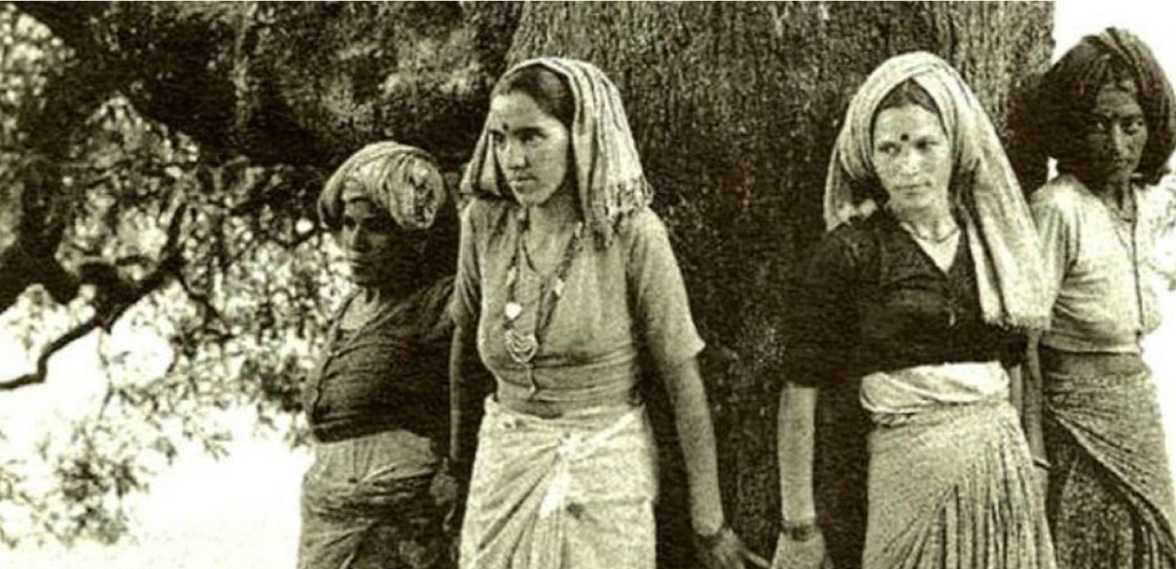

For generations, environmental protection in India was not a matter of international obligation but an act of everyday survival. It was practised by women tending forests, by tribal communities safeguarding sacred groves, by farmers managing water and soil in tune with seasons. These were not campaigns, they were cultures. And they shaped a powerful grassroots legacy of environmentalism that continues to guide us.

At Oneworld Colab, we believe this legacy is not just a memory, it is a mandate.

As India races to meet its climate commitments and development aspirations, we must not ignore the truth that the most impactful environmental solutions have come from the ground up. Especially from women, who despite being central to climate resilience are consistently excluded from climate planning, finance, and leadership.

This World Environment Day, we reflect on India’s unique trajectory of ecological resistance and regeneration, and call for a new climate paradigm, one that recognises, resources, and restores the role of communities at the front line of climate change.

India’s Environmental Journey: A People’s History

India’s environmental movements did not begin in boardrooms or think tanks. They began in forests, villages, and river valleys, places where land and livelihood were inseparable.

As early as 1730, the Bishnoi community in Rajasthan staged what is now recognised as one of the world’s earliest environmental protests. When royal loggers came to cut trees in their village of Khejarli, Amrita Devi and hundreds of Bishnoi women and men hugged the trees, choosing death over ecological destruction. Their sacrifice led to a royal decree protecting the region’s flora and fauna. Long before the word “sustainability” entered global lexicons, India’s rural communities were practising it.

In the 20th century, the colonial state’s forest laws triggered the Forest Satyagrahas; nonviolent protests in Maharashtra and Karnataka, where tribal and peasant communities defied British restrictions on forest access. These actions were not only environmental in nature, but they were expressions of autonomy, land rights, and food security.

The post-independence era brought a wave of organised people’s movements, the most iconic of which was the Chipko Movement in the 1970s. In the hill villages of Uttarakhand, when commercial logging threatened the subsistence economy, women led by Gaura Devi physically embraced the trees to prevent them from being felled. Their courage catalysed public discourse on deforestation, inspired similar movements like Appiko in Karnataka, and eventually influenced the passage of the Forest Conservation Act of 1980, which restricted forest land diversion.

In Kerala, the Silent Valley Movement of the 1980s saw scientists, teachers, tribal leaders, and poets join forces to protect one of the last remaining tropical rainforests from a proposed hydroelectric dam. Their victory helped conserve a biodiversity hotspot and underscored the power of science-backed, people-led mobilisation.

Further west, the Narmada Bachao Andolan, launched in the mid-1980s and led by Medha Patkar, opposed the displacement of tribal and farming communities by large dams on the Narmada River. The movement, while not successful in halting all dam construction, fundamentally altered how India understood “development,” spotlighting the human and ecological costs of mega infrastructure.

Throughout these decades, hundreds of local and regional actions continued, from Jharkhand’s Jungle Bachao Andolan to the recent Save Aarey Forest campaign in Mumbai and the ongoing resistance in Hasdeo Arand, where Adivasi women are leading the fight against coal mining in one of Central India’s densest forests.

The Evolution of Policy: An Emerging Partnership

India’s policy and legal framework regarding environmental issues has shown growth as it increasingly aligns with the demands of its citizens. Over the years, vibrant citizen movements have played a crucial role in driving significant legal advancements, fostering a collaborative approach to environmental stewardship.

But a lot is still left to do on the policy front as the climate challenges becomes more urgent and complex.

The Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 marked the first major post-independence legislation to protect biodiversity. The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act (1974) and the Forest Conservation Act (1980) followed. In 1986, after the Bhopal gas tragedy, the government passed the Environment Protection Act, offering a broad framework for pollution control.

The Biological Diversity Act (2002) was introduced in response to the global Convention on Biological Diversity, and the Forest Rights Act (2006) finally acknowledged the historic land rights of tribal communities. In 2010, the National Green Tribunal was created as a specialised judicial body to handle environmental cases.

Yet implementation has remained uneven. Many policies were written without the full participation of affected communities. Legal provisions exist, but when women farmers in drought-affected regions or forest-dwelling tribes seek to exercise their rights, the systems often fail them.

This is the disconnect Oneworld Colab seeks to bridge: aligning state ambition with ground reality, and ensuring that those who protect nature are also empowered to shape its future.

Women: The Unrecognised Architects of Sustainability

Across every movement mentioned above, the most consistent presence has been women. In Chipko, they were the ones who stood between axes and trees. In the Narmada valley, it was women who documented displacement, organised marches, and maintained protest camps. In Aarey and Hasdeo, they continue to confront corporate and state interests, despite risk and harassment.

Why? Because women are often the first to feel environmental degradation. They fetch water, manage food and fuel, and care for families. When forests disappear or rivers dry, their labour and wellbeing are directly impacted. Yet global climate finance allocates less than 0.2% to women-led initiatives. In India, women form 42% of the agricultural labour but only 11% of the solar energy workforce. Women-headed households suffer up to 30% more crop loss in climate disasters. (Sources: OECD 2024, IRENA-FAO 2024, ICRW 2023*)

We cannot build a climate-resilient India by excluding those most affected by climate impacts, the women.

Where We Are Now: A Critical Juncture

India is warming faster than the global average. Heatwaves are longer, more frequent, and deadlier. Flash floods, failed monsoons, and sea-level rise threaten both rural livelihoods and urban infrastructure. At the same time, India has made bold climate commitments: achieving net zero by 2070, transitioning to renewables, and leading international initiatives like the International Solar Alliance.

But these ambitions will only succeed if they are grounded in inclusive systems.

Too often, climate programs are centralised, top-down, and technical, disconnected from the people who will live with their consequences. Funds don’t reach local actors. State programs fail to reflect gender dynamics. Traditional knowledge is ignored in favour of imported solutions.

The risk isn’t just inefficiency, it’s injustice.

A Call for Regenerative Climate Action

India’s ecological future is inseparable from its people’s enduring legacy of stewardship and people’s movements. While policy frameworks and technical expertise play vital roles, the true architects of India’s environmental journey are the grassroots leaders—the Bishnoi women of Rajasthan, the Hasdeo protestors, the water warriors, and the countless women who manage forests and farms with resilience and wisdom, often unrecognised as “climate leaders.”

This World Environment Day, let’s:

- Recognise and celebrate India’s rich, people-led environmental history. Acknowledge the contributions of local communities, especially women and youth, whose lived experience has shaped the nation’s ecological consciousness.

- Invest in women, youth, and community-led climate solutions. Empower those closest to the land and water to drive innovation and adaptation.

- Design policies that reflect real-world experience and local knowledge. Move beyond data models to integrate the insights and needs of those most affected by environmental change.

- Shift from top-down implementation to co-creation and partnership. Foster inclusive decision-making processes that centre the voices of marginalised and front line communities.

Climate change is not merely a technical challenge, it is a complex, interconnected issue that demands solutions grounded in justice, equity, and innovation. At Oneworld Colab, we are committed to supporting this transformative shift. A truly regenerative future does not erase the past; it builds upon the lessons and leadership of those who have always protected India’s natural heritage. Together, we can ensure that the next chapter of India’s environmental story is written by and for its people.

Let’s begin there.